Why the coal industry should hope that it's efficiency and renewables that displace coal-fired generation

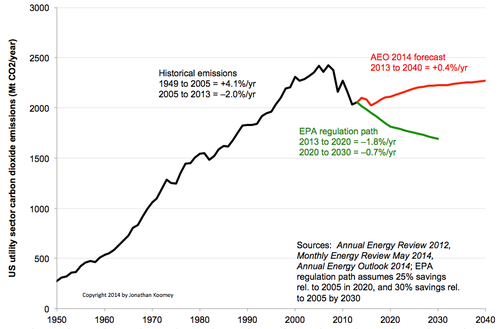

To give context to the recent EPA proposed rule on existing power plant emissions, this week I compiled historical data and the most recent Energy Information Administration (EIA) projections on carbon emissions for the US utility sector. The results are shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1: US utility sector carbon dioxide emissions over time (Mt carbon dioxide per year)

The historical data for utility sector carbon emissions (which includes independent generation sources) through 2011 come from the Annual Energy Review, The historical data for 2012 and 2013 come from the May 2014 Monthly Energy Review. The business as usual forecast for 2014 to 2040 (assuming no changes in current policy, published well before the proposed EPA rules), comes from the Annual Energy Outlook 2014.

I estimated the emissions path for EPA’s proposed rule by assuming that total utility sector emissions would hit 25% below 2005 levels by 2020, and 30% below 2005 levels by 2030, based on a Wall Street Journal article about the rule. I then linearly interpolated between 2013 and 2020/2030 emission levels.

Historical growth in emissions averaged 4.1%/year from 1949 to 2005. Total emissions remained about the same through 2007, then dropped rapidly, falling more than 2%/year starting in 2007. Some of that decline was caused by the Great Recession, some by efficiency improvements, some by switching to natural gas, and some by increased penetration of renewables.

The EIA’s business as usual projection shows growth in utility emissions of about 0.4%/year from 2013 to 2040, while the EPA regulation path shows declines of about 1.8%/year through 2020 and 0.7%/year after that. So the first years of the rule to 2020 are estimated to result in a annual rate of decline in emissions slightly less than that experienced between 2007 and 2013.

What I realized in compiling these numbers is that the coal industry should hope that the utility industry uses non-fossil resources (like renewables and efficiency) to displace coal plants and meet the constraints of the rule. By 2020, emissions will need to decline by about 12% compared to 2013, which means an absolute reduction in annual emissions of 240 Mt carbon dioxide per year.

If that reduction in coal use (which represents about 15% of US coal generation in 2013) is brought about by efficiency and renewables, then only 15% of coal plant generation existing in 2013 would be displaced. If instead the coal reductions come about from using natural gas in advanced combined cycle power plants, then utilities would need to displace twice as much coal to achieve the mandated emissions reductions, because natural gas fired generation emits half as much carbon dioxide per kWh as coal (this ignores the still live issue of fugitive emissions of methane, which are almost certainly higher than official estimates, and would make this problem even worse).

So once the coal industry accepts that emissions have to come down, and eventually they will, then their natural temporary allies in a scenario of declining coal production (or at least their somewhat less hated opponents) are wind generators, photovoltaic panels, nuclear power plants (if we can build them on time and on budget), and efficient appliances. Weird, huh?

For those who want to review my spreadsheet and check the numbers for yourselves, download it here. It has the AEO 2013 and 2014 year by year numbers, which you can’t get from the official EIA reports. It also contains the graph above for ease of use. Feel free to reproduce the graph as long as you link back to this post and acknowledge the source.

As an aside, this analysis method is another example of “working forward toward a goal”, a general approach that I explore in Cold Cash, Cool Climate: Science-based Advice for Ecological Entrepreneurs and my recent article in Environmental Research Letters titled “Moving Beyond Benefit-Cost Analysis of Climate Change”.

Addendum, Jun 6, 2014: One of my most astute colleagues pointed out that the EPA rules are specified in terms of emissions rates, rather than absolute emission levels, and the connection between renewables and efficiency to meeting the standards is more complicated than I indicate above. The general lesson still holds, as long as you are thinking about absolute caps on emissions (as the Northeast US and California are doing) but the exact implications need careful study for the US as a whole. Live and learn!